I have a few friends who are in the midst of navigating very hazy idea spaces, guided by strong intuition and taste, but early enough in the process that very little is visible through the fog. Whenever I’m in this situation I feel a strange internal conflict. One side of me feels conviction in a direction of exploration, while the other part of me feels the risk of potential dead ends, afraid to go out on a limb and say I should put my full effort into pursuing where my hunch leads.

In fact, I’m navigating a version of this conflict right now:

- I feel strong conviction in the potential of using AI interpretability techniques to uncover new ways of seeing and expressing our ideas.

- The research is so new, the field so young, and the use cases so unclear that it feels quite likely I may chase this idea and arrive at nothing valuable, let alone transformative.

Last week, I was catching up with one of my friends going through something similar, and ended up describing to them a mental model of exploration that I’ve developed in the hopes that it was helpful. It’s a framework I think my past self would have found meaningful, so I’m also sharing it with you, dear reader.

Let’s begin by understanding that exploration is far from the only way to do meaningful creative work in the world. Following popular rhetoric, it was easy for my past self to fall victim to the idea that somehow exploratory, open-ended, research-y work was more virtuous and interesting than the work of incremental improvements. On the contrary, I now think it’s quite likely that most valuable things were brought into this world by a million little incremental improvements, rather than by a lightning strike of a discovery. Incremental work can be just as rewarding as exploration. When you work in a known domain:

- You can understand everything in your field much more deeply than in a field of unknowns. Chances are good that there is deep history, drama, and technical details in every little corner of your world, and this chance to chase down rabbit holes to the end of our knowledge can feel really rewarding.

- Your results are more predictable. You may not know exactly how you’ll solve a problem, but perhaps you know exactly how completely you need to solve it. Or you know exactly how valuable a solution would be. Or you know exactly who needs your solution the most. Working in an established space, your constraints are more predictable, and they let you take very targeted, narrow risks to attack problems deeply.

But you’re not here to work on optimizing what’s known. You’re here because something about the process of exploration draws you in. Maybe it’s the breadth of ideas you encounter in exploration. Perhaps it’s about the surprising things you learn on the way. But you’ve decided you’re more interested in navigating and mapping out unknown mazes of ideas than building cathedrals on well-paved streets.

Here’s what I would tell my past self:

If you’re on this path of exploration, there’s probably some voice inside of you that’s worth listening to. This is your taste, your gut feeling, whatever you want to call it. It’s the part of your intuition that tells you, “this might not look that great right now, but on the other side of this uncertain maze of ideas is something worth the trouble.” It’s worth listening to your intuition because this is what’ll set your perspective apart from everyone else who’s also looking around for problems to solve. In the beginning, your intuition is all that you have as you begin your exploration.

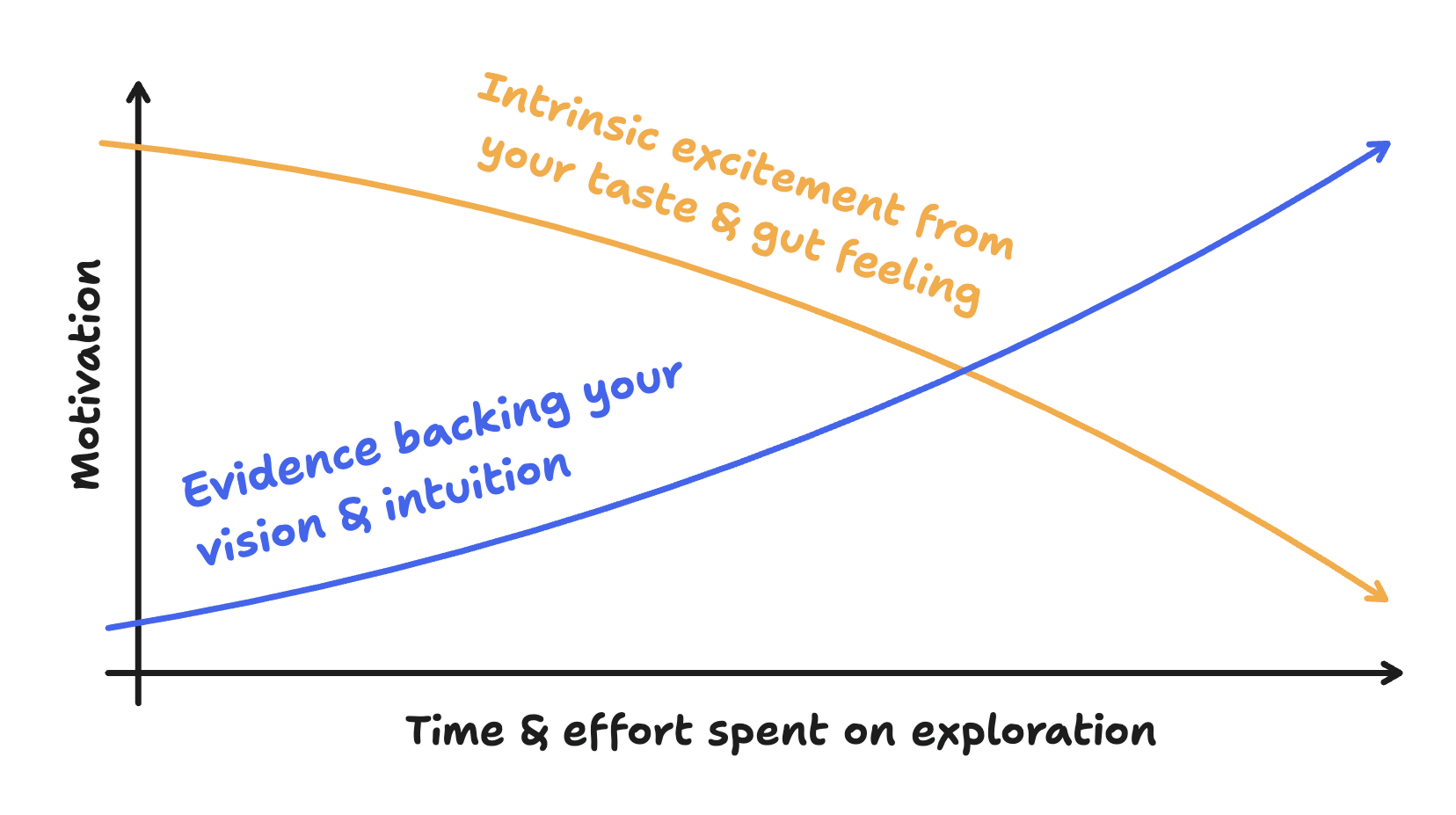

This voice — your intuition — is strongest at the outset. At the start of your exploration, when you have very few hard facts about what will work out in the end, you can lean on your inner voice, and the intrinsic excitement you feel about the potential of your idea, to keep you going. Nearly all of your motivation comes from your intuition at the starting line.

But excitement from your intuition is volatile. As time passes, and as you run experiments that don’t succeed, that innate excitement you felt at the beginning will begin to dwindle. To keep your momentum, you need to replenish your motivation over time with evidence that backs your intuition and your vision.

There are many short-term faux-remedies to faltering intrinsic excitement — raising money, external validation, encouragements from friends and family — but all of these are like borrowing your motivation on debt. Eventually, they’ll run out, and you’ll be left with a bigger gap you need to fill with real-world evidence of the correctness of your vision. The only way to sustain your motivation long term is to rapidly replenish your excitement and motivation with evidence that your vision is correct.

Evidence comes from testing clear, falsifiable claims about your vision against the real world.

For my personal explorations, here’s a claim that I can use to find evidence to support my vision:

By using interfaces that expose the inner workings of machine learning models, experts in technical and creative jobs can uncover insight that was otherwise inaccessible to them.

This claim can still be more precise, but the bones are there. I can polish this into a testable statement about the real world, build prototypes, put it in the hands of experts, and collect evidence supporting my vision that interpretable machine learning models can be a foundation for transformative new information interfaces.

Very frequently, your initial claim will turn out to be incorrect. This doesn’t mean your vision is doomed. On the contrary, this often gives you a good opportunity to understand where your intuition and the real world diverged, and come up with a more precise statement of what initially felt right in your gut. While collecting evidence that supports your vision motivates you towards your goal, finding evidence that contradicts your claim can bring much-needed clarity to your vision.

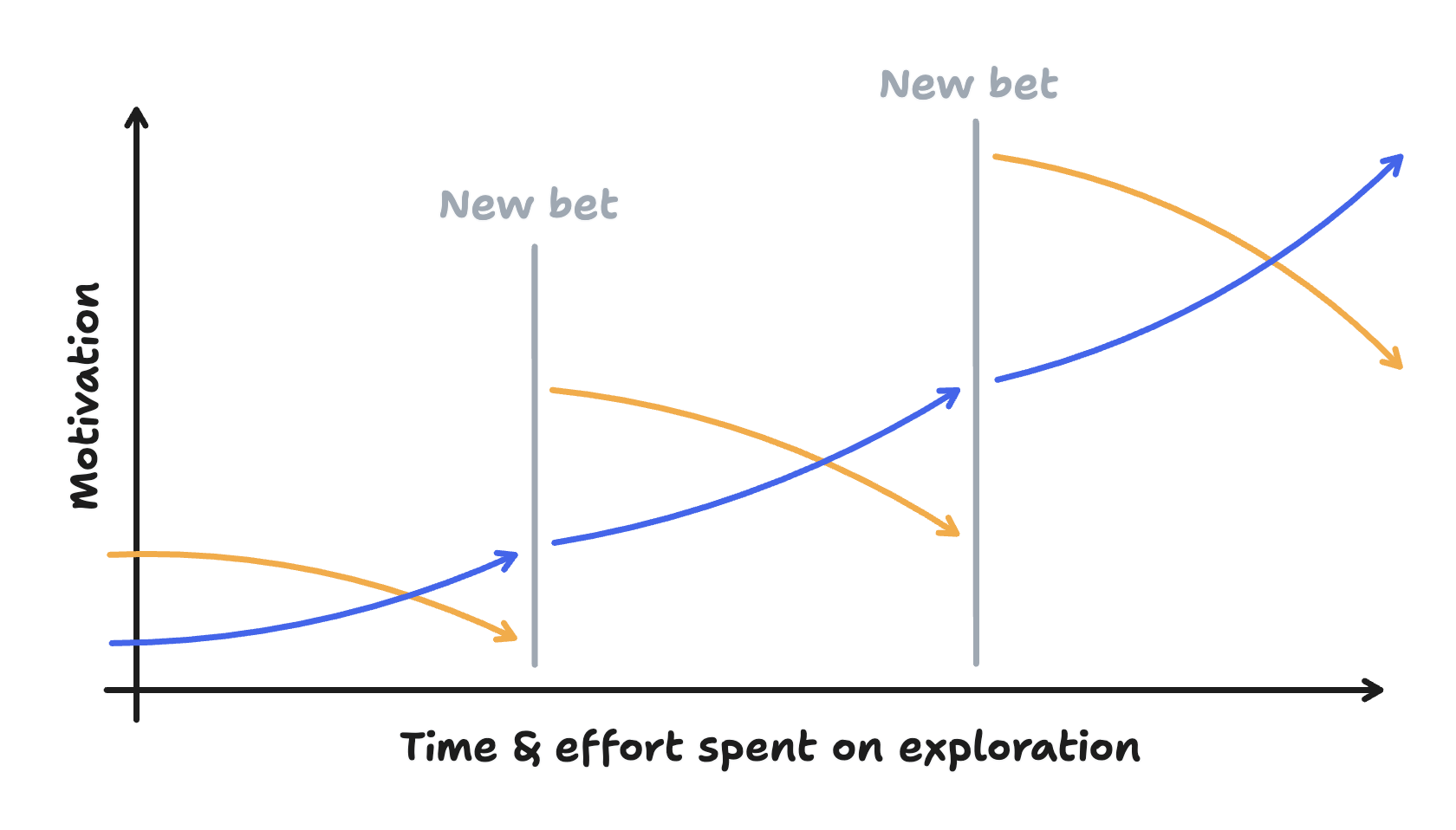

Once you’ve collected enough evidence to support your initial vision, you’ll often see that the answers you found through your evidence-gathering experiments gave rise to many more new bets you’re interested in taking. That same taste for good ideas you had in the beginning, now strengthened by repeated contact with reality, sees new opportunities for exploration.

So the cycle repeats. On the shoulders of your original vision, which is now a reality after all the evidence you’ve collected, you can make a new bet, starting with a renewed jump in motivation. You can collect more evidence against this new vision, and on and on.

All the skills involved in this cycle — clearly stating a vision, tastefully choosing an exploration direction, and collecting useful evidence from reality — will get sharper over time as you repeat this process. Every time you make a new bet on a new idea, you’ll be able to take bigger swings.

If you look at this chart a little differently, this story isn’t about making many disparate bets in a sequence. It’s about bringing the world towards your ever-more-refined statement of your vision. Every piece of evidence you collect to support your vision will be another stair step in this upward motion, and over time, the world behind your experimental evidence will come to resemble the world you originally envisioned.

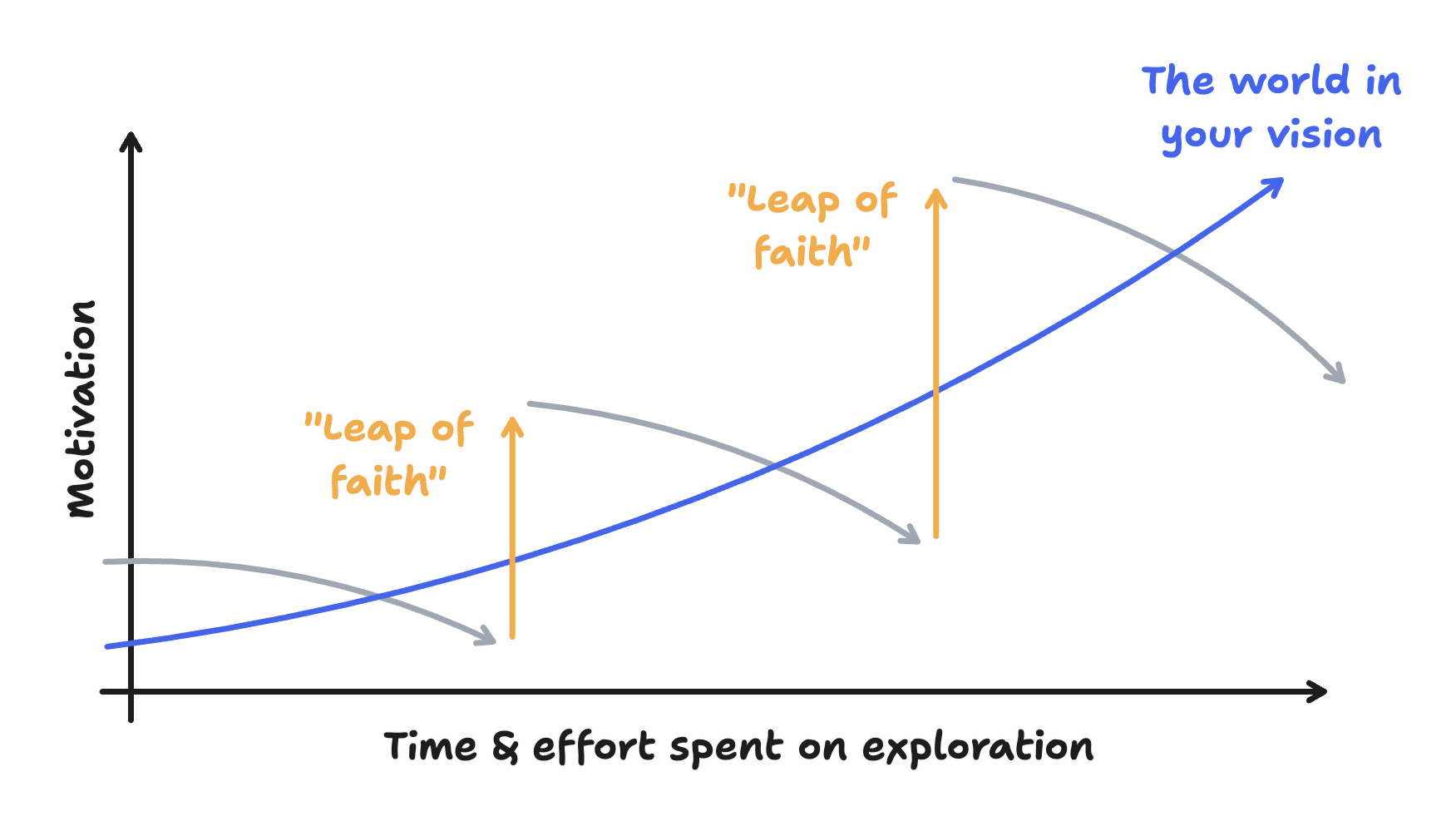

In this process, you’ll periodically have to find new ideas that give you motivation to take on those new bets. These are what someone else may call “leaps of faith”, but I don’t like that expression. A “leap” makes it sound as if the motivation is coming from nowhere, and you should blindly jump into a new idea without structure.

But there is structure. The “leap” is guided by your intuition and aimed at your vision, and as your internal motivation runs out, you’ll collect evidence from reality to close that gap.

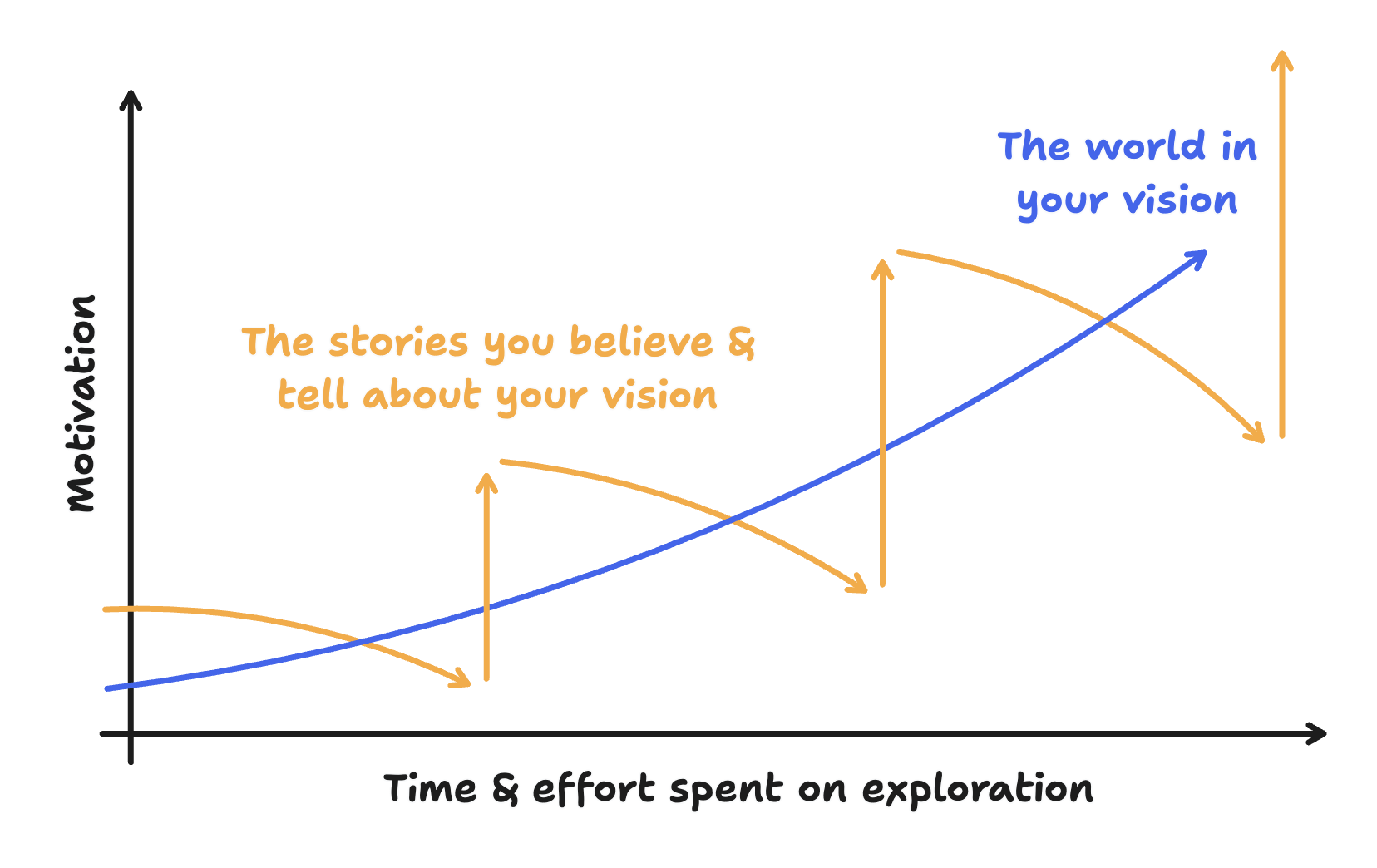

Taking a step back, I think there’s another helpful perspective we can find. Chasing a vision is about a dance between two forces: the stories you believe and tell about a world you envision, and the world you build on top of reality to follow that story.

Your stories draw on your taste, your experience, and your intuition. These stories need to bottle up the special things that you’ve seen in your life that others aren’t seeing, and compel yourself and others to work through the process of turning that motivation into evidence.

Your evidence, in turn, needs to continually close the gap between reality and your storytelling. Over time, as your stories and your reality evolve around each other, you’ll bridge the distance between your vision and the real world.

This is all well and good as a way of thinking about exploration at a distance, but when I’m buried in the thick of confusing experiments and dwindling motivation, it’s difficult to know exactly what I need to do when I wake up in the morning.

During those times, I focus on two things:

- Clarity of vision and sharp storytelling. In the face of new bets or lackluster evidence, your success depends on how well you can convince yourself and others around you that there’s something worth digging deeper for just around the corner. You can do this by investing in clearer vision, communicated with sharp storytelling. If you’re finding that your evidence supports your vision, incorporate that evidence into your storytelling to move faster.

- Momentum behind my exploration, which is the best way to ensure you can convert your energy into useful evidence to support your vision. In open-ended exploratory search for good ideas, it’s hard to know exactly which next experiment is going to yield fruit. During these times, rather than trying to make every individual step successful, it’s better to invest in breadth and coverage of your exploration, and keeping momentum up will help you continue to cover new ground until you hit on the right evidence.

I find my life and work most invigorating when I can work next to people on exploratory paths. There is no special virtue in novelty or risk-taking, but exploratory work often leads to surprising new facts about how the world works, and if those surprises are well leveraged, exploration can yield transformative progress. At a personal level, I also find myself having the most fun when I get the fortune of working next to people doing exploratory work.

If you find yourself in such a path, as I do, I hope this way of thinking about your path ahead helps take some of the burden off your shoulders, and allows you to shape the world to your ever sharper vision for what ought to be.

Thanks to my friends at UC Berkeley for discussions that ultimately sparked this blog post. You know who you are.

← A notebook for seeing with language models

Instrumental interfaces, engaged interfaces →

I share new posts on my newsletter. If you liked this one, you should consider joining the list.

Have a comment or response? You can email me.