There’s a resurgence in products using text as the primary user interface.

The most popular tool that uses text as a core UI is probably Microsoft Excel. Excel is a mostly-WYSIWYG application, but when interacting with formulas and programming cells, the interface of choice for most users is text – typing in formulas as textual information, not clicking buttons. When we want to take the sum over a row, most of us click on the cell and type =SUM(A3:A10) – we don’t click on a “sum” button or unfurl a dropdown menu.

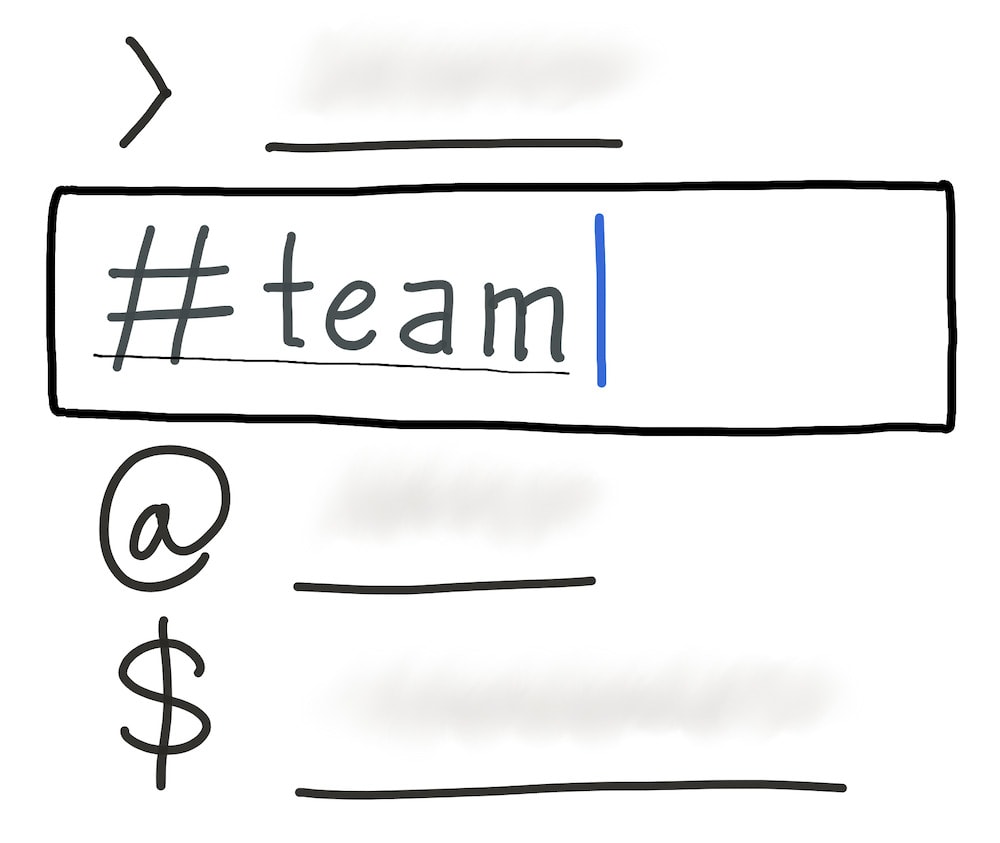

The poster child of textual user interfaces is the command line in the terminal. But I think a new crop of tools, combined with a more tech-savvy market, is staging the rebirth of text as a user interface. Textual interfaces are everywhere in the modern workplace. Slash-commands in Slack and Discord and Notion, hash-tags for channels and tagging, special syntax for searching and querying data across applications, @-mentions in social media and team work environments, and so on. We’re training ourselves to be more savvy users of the textual interface.

The forces at work

I think we’re seeing textual interfaces rise in popularity wherever people look for any of the following.

Progressive feature discovery

Text interfaces within graphical UIs gained popularity in places with a high feature-to-visual-complexity budget. In other words, when there’s many more features than can fit comfortably on the screen at once, we hide that surplus complexity behind text options.

In many tools with a high degree of hidden complexity, the average user uses only a small subset of those features frequently. A Slack workspace, for example, might have a hundred slash-commands enabled, but each individual team member may only frequently use 5-10 of those commands on a regular basis. Rather than clutter up the interface with a hundred buttons or a web of dropdown menus, we hide the complexity behind text options, and the user can learn the few features they use most frequently, so they can access them again easily.

This idea applies to tools with a lot of complexity, where any single user might only take advantage of a small subset of that feature set. I think more tools are falling into this bucket as productivity tools consolidate. If a single kind of interface is shared by all business-chat clients, or all product-management tools, or version control software – rather than building custom interfaces for each workflow or use case, why not provide a wide surface area of functionality that’s accessible via text?

Extensibility and the portable interface

Modern software workflows cross application and service boundaries all the time. Textual interfaces provide an enforceable, rigorous contract between services and applications that can act as the interfaces for apps to integrate with external services, in a way that visual interfaces can’t.

In a software development team, a proposal for a bug fix might flow through a task tracker, which connects with a team messaging app, where an engineer might run a group poll or lead a discussion. The request change might flow back into the task tracker, into a version control system like GitHub, and then deploy automatically to production servers.

Workflows like this require that apps from completely different vendors and domains are able to communicate with each other. More importantly, it requires that the interfaces we use to control these tools be portable. A portable interface carries the same kind of UI across different services, so the user can interact with any service similarly across all of its integrations. Portability means that we can enter data into our task tracker through our chat client, or request the rollout of a change through an infrastructure provider from our version control system.

These integration points are much easier to build, and easier to master as end users, when they all share the same, portable format – text.

Automation

Textual interfaces make automation trivial, and automation tools much easier to build.

More people are using tools like Zapier and Alloy to automate common business tasks or link very domain-specific workflows together across services. Having a shared portable interface across these apps, and a syntax format that can serve as a contract for how to use that interface, makes it possible for these automation points to communicate to dozens of other services easily. It also minimizes the possibility that a future update to the UI might break an automated workflow.

Text interfaces are much easier for machines to use. And as more work is done autonomously by the workflows we teach machines to perform, text interfaces are starting to matter just as much as human ones.

Sharability

People naturally want to document their workflows to remember, share, and iterate upon as a team. To share a graphical workflow, I’d need to record my screen or spend time writing down instructions for how to navigate a visual interface, clicking the right buttons and checking the right boxes. Reifying workflows as text makes this much easier – I can just encode a workflow into a few lines of text input.

In this way, workflows driven by text interfaces are easier to share, document, and iterate over time within a team. Text interfaces make workflows more concrete.

Workflows, not data, are the subject of innovation

Given these benefits of text as an interface, weighted against the very real cost – text is a more esoteric way to use a computer – why are we seeing a resurgence in this trend now?

I think the easiest factor we can identify is that more people entering the workforce are unafraid of textual interfaces, because they’ve been typing and messaging and tagging their friends online all their life. They already interact with computers via text.

But the second reason that’s driving the industry to text is that the focus of software services has shifted from manipulating data to manipulating workflows. We’ve learned how to store and sift through data in our computers as a society, so we’re moving up a step of abstraction, to storing and sharing the how’s of our work, not just the what’s.

Workflows, not data, are the subject of product innovation now. And the subject is easier to study, to compare, to share and extend, when it’s concrete and durable, not an organic, ephemeral series of actions.

I think as long as we’re innovating on how we work, and how the services we use can work together more effectively, text as an interface is here to stay. And why not? The software industry has spent the last half-century building tools to help us wrangle with text, and we can rediscover those tools and ideas again.

We’re entering a renaissance of user interfaces, not in the sense of a novel paradigm shift, but in the sense of a rediscovery of classic, enduring ideas on which we can build better tools and systems. And I, for one, welcome it.

In defense of natural language →

I share new posts on my newsletter. If you liked this one, you should consider joining the list.

Have a comment or response? You can email me.