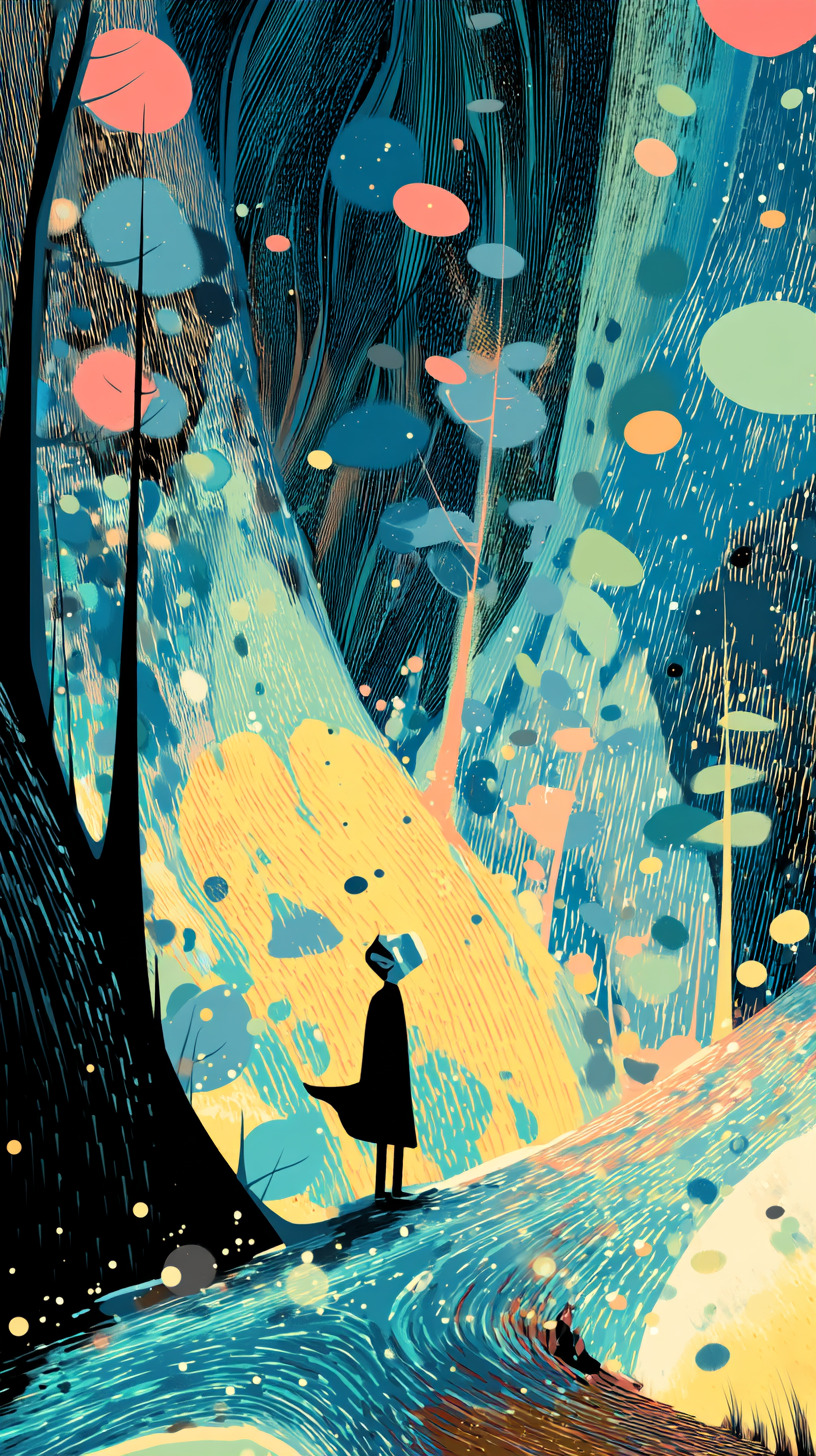

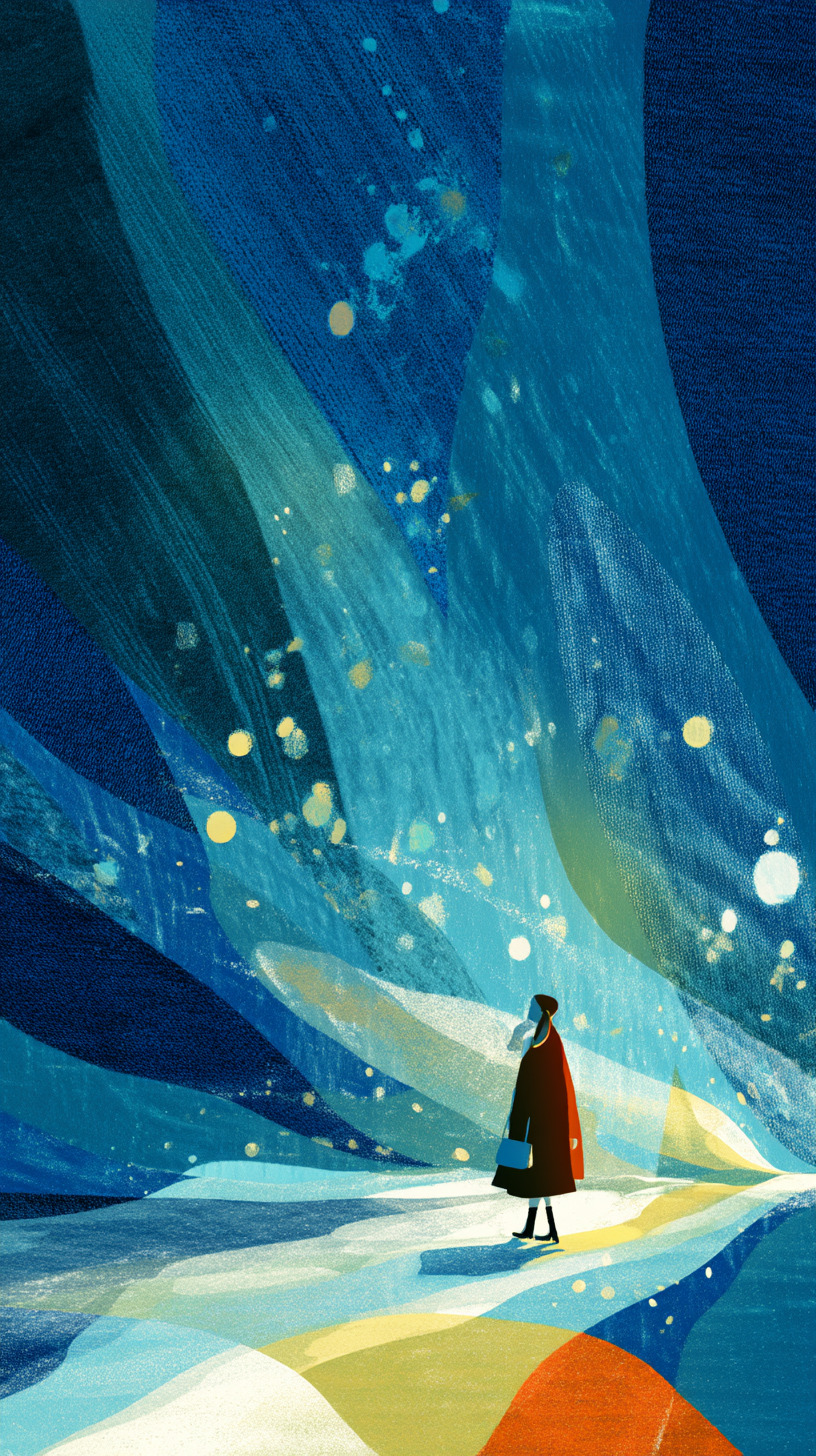

I will never forget the first time I watched Soul.

It was not the haunting soundtrack from the Reznor and Ross duo nor the whirlwind storyline that glued my eyes to the makeshift projector wall I had fashioned last minute out of my window curtains but this:

I mean–

How do you, as an ordinary mind walking around the physical world, surrounded at every turn with mundane, opaque objects fastened to the banal constraints of our three dimensions and material world–

How does one even begin to imagine this visual? This form?

I found myself sinking into the beauty and novelty of these figures, not quite one-dimensional line drawings and not quite two-dimensional ghosts. I talked about it to many friends. It was as if I had tripped and fallen into a completely new possibility of form. A way of being a shape and taking up space so hidden in between the density of familiar shapes that I didn’t even realize there was newness to excavate.

In anther fictional universe the protagonists of Greg Egan’s Luminous burrow into the cracks of a much different space of possibilities. Digging around (figuratively speaking, with their optically-operated supercomputer) in the space of possible mathematical statements the find bubbles of self-contradiction, a kind of fissure of falsehoods in the otherwise dense and uniform space of mathematical truths self-evidently derived from fundamental axioms, where “two and two make five.”

As the supercomputer churns through giga-proofs every second, Egan describes a computer display visualizing a visual map of the space of all mathematical statements, and a region of the map blossoming outwards, claiming dark patches of knowledge as self-consistent with the fundamental axioms of mathematics.

|

|

|

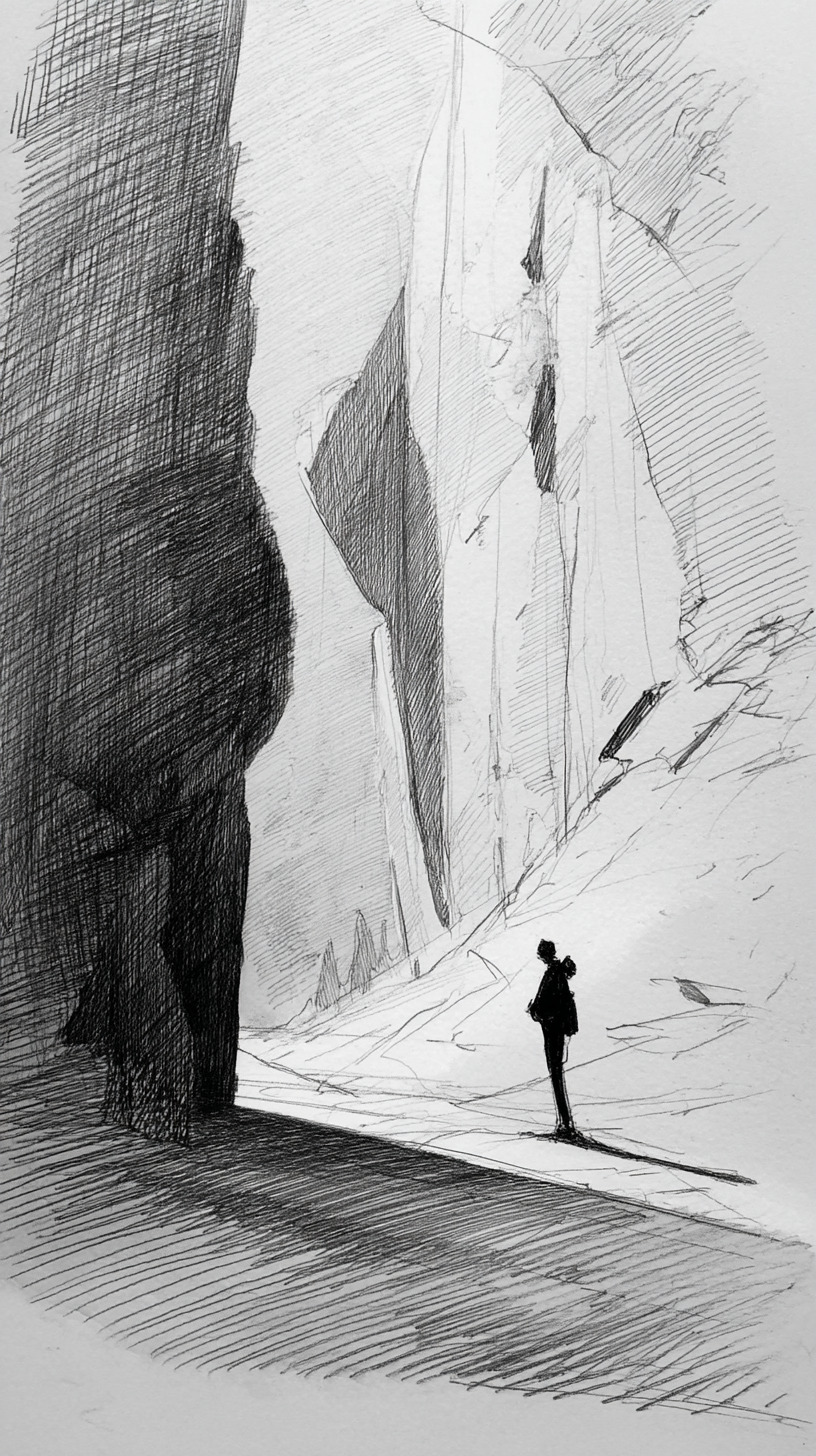

I have long been drawn to physical depictions of spaces of knowledge. My favorite work of Egan, Diaspora, contains my favorite instance of this, the “truth mines” where sentient beings labor in a computer-simulated underground cave network chipping away to discover new mathematical insight.

Yatima, whom the reader is following through this passage, observes

A single tunnel led into the cavern, providing a link to the necessary prior concepts, and half a dozen tunnels led out, slanting gently “down” into the bedrock, pursuing various implications of the definition. Suppose T is a topological space…then what follows? These routes were paved with small gemstones, each one broadcasting an intermediate result on the way to a theorem.

Yatima observes quickly that this exercise of intellectual exploration could be delegated to efficient computer programs, a crowd of exponentially numerous “moles” to search the caverns for useful truths. To which Radiya, their guide, explains

If we were insane enough, we could try turning the whole planet – or the whole galaxy – into some kind of machine able to exert the necessary brute computational force…but even then, I doubt we’d reach Fermat’s Last Theorem before the end of the universe.

Instead, the miners chip away at the border between the well-known and unknown only at the speed at which their mind can grasp and map the space of known mathematics, their mental models learning and adapting in real-time rather than simply brute-forced by a machine then grafted onto their worldview.

Whether mathematics could be mechanized in this way or not, this vision of the space of knowledge as a concrete world through which I could explore and map captured me for many years thereafter.

In these visions I fell in love with the idea that there was some quality other than truthiness that ought to guide our search for knowing more about the universe and about living. This ineffable quality I’ve come to call by many names. Among them are words like novelty, surprise, and wonder.

|

|

|

Wonder is what guides my search for meaningful problems to work on. Is what appears in the problem description all there is? Or is there something surprising or new to be learned? Will I emerge from this particular branch of the truth mines with a map that’s not just bigger, but somehow feels more satisfying and more fundamental?

At the start of the year, I spent many hours listening to talks and reading about different areas of modern pure mathematics, primarily number theory and topology. As a lay observer, I found both of these branches of math to feel like a process of unraveling cosmic structures out of some incredibly high dimensional ball of yarn.

Number theory begins with one of the most basic objects in all sciences, the integers. Then, by stacking thin layers of complexity on top of each other like addition and multiplication, the primes, and various kinds of infinities, number theorists are able to back out a stunningly rich map of statements about sets of numbers with different properties and how they might relate to each other in completely unexpected ways. The most famous among them is the Riemann zeta function, a simple-looking infinite sum of fractions that turns out to have surprising implications in something completely unrelated: precisely how “dense packed” the prime numbers are as we count up towards infinity.

What I find most compelling about this kind of domain of study is that there appears to be an infinite capacity for wonder and surprise – infinite capacity for holding the unknown but satisfying – in a space defined from a set of axioms you could count on one hand.

Closer to my home field, there are aspects of software and computing that feel similarly rich in wonder, like the concept of superposition in mechanistic descriptions of deep learning models or computational complexity or compiler optimizations. In each of these spaces there appears to be an unbounded capacity for discovering some new knowledge seemingly manufactured out of nothing but mere exploration.

I spent nearly the last decade of my working life driven by a kind of obsession over things I create that compelled me to sprint at every opportunity to the end of the next lap. To solve the next logical follow-up research question. To fix the next bug. To write the next essay. This certainly got me pretty far with a lot of creative exhaust produced along the way, but I much prefer my more recent way of working, where I try to spend as much of my time every week as I can manage on being pulled into problems by virtue of their capacity to contain wonder and compel my curiosity, rather than being thrust into them by my inability to leave ideas unfinished.

|

|

|

This same capacity for wonder is also what I have come to search for in people, sometimes even against other more concrete qualities like raw intelligence or accomplishment. I find myself most fulfilled when I am around people who are in pursuit of wonder, and inspire it in myself.

If wonder manifests as a kind of capacity for infinities in the domain of problems, in the domain of people I observe wonder as a kind of life force propelling people through their days. A twinkle in someone’s eyes when they begin to talk about something.

It’s not quite curiosity, which I view as more innate to humanity, but rather an innate ability to be drawn by curiosity about the right kinds of things. A taste in subjects of curiosity, perhaps.

I find that even in brief conversations of a few minutes, I can tell whether someone is propelled through the world by wonder or by something darker like self-uncertainty or more blind desire to win. There isn’t anything necessarily wrong with other more exogenous motivators for great work, like obsession or social pressure or a desire to be the best. But those remind me of the more “brute force” approach to scavenging the truth mines for knowledge, which misses what I feel is the point of learning and creating.

In many of my favorite people the wonder spills out of them effortlessly. A slight conversational tug on the mention of a book they read last week or a film they’d like to watch compels forth a whole cinematic universe of related questions, idle ponderings, shower thoughts, deep curiosities behind their lifework.

|

|

|

I’ve also spent a lot of my life thinking about a virtue that I consider the perfect foil of wonder – productivity. Pursuit of bare productivity often manifests as an extractive endeavor: how can we take something we are doing today, and make it more efficient, more scalable, more predictable? Productivity is about the industrialization of creation. Wonder, in contrast, defies systematization because it gets its power from uncertainty and surprise by nature. You can’t optimize wonder, because to optimize requires knowing the output and the process. Wonder is the discovery of new outputs and new ways of getting there.

Within my corner of the world of knowledge tools and artificial intelligence the dominant narrative seems to be about the promise of these technologies in the game of productivity and industrialization. People are eager to reduce, make more affordable, and produce more. I am sure all that will happen, but I think this ignores the fact that the most interesting ways in which civilization advances is through discovery guided by wonder. There are totally new kinds of ideas and aesthetics and ways of spending our time that are beyond the frontier of our understanding. Every time I see yet another attempt at forecasting economic productivity improvements from technological progress I feel that they are methodologically bound to only measure changes to the world as we conceive of it today.

Like the computations of the Luminous supercomputer propelling the frontier of mathematical theorems forward in the space of facts, I dream of tools that can illuminate new understandings of what it means to be born into this universe and spend time within it.

|

|

|

On the front page of my website, at least at time of writing, is the first paragraph is a personal mission statement I’ve grown fond of through the last few years. It ends with:

I prototype software interfaces that help us become clearer thinkers and more prolific dreamers.

The former, “clearer thinkers” is intuitive and obvious. I’ve worked on many projects trying to help people learn faster or come to more informed conclusions about the world. The latter I’ve spoken less about due to its ambiguity, but I feel I’ve found a way to capture it that does the delicate construction of the phrase justice.

Capacity for wonder – tasteful curiosity that opens up rich new universes of wisdom – is the most fulfilling and productive renewable resource I know of in the world. I want to surround myself and fill my life with engines of wonder, whether people or problems. And I want to work towards a world where wonder is as worthy and celebrated a pursuit as creativity or productivity.

|

|

|

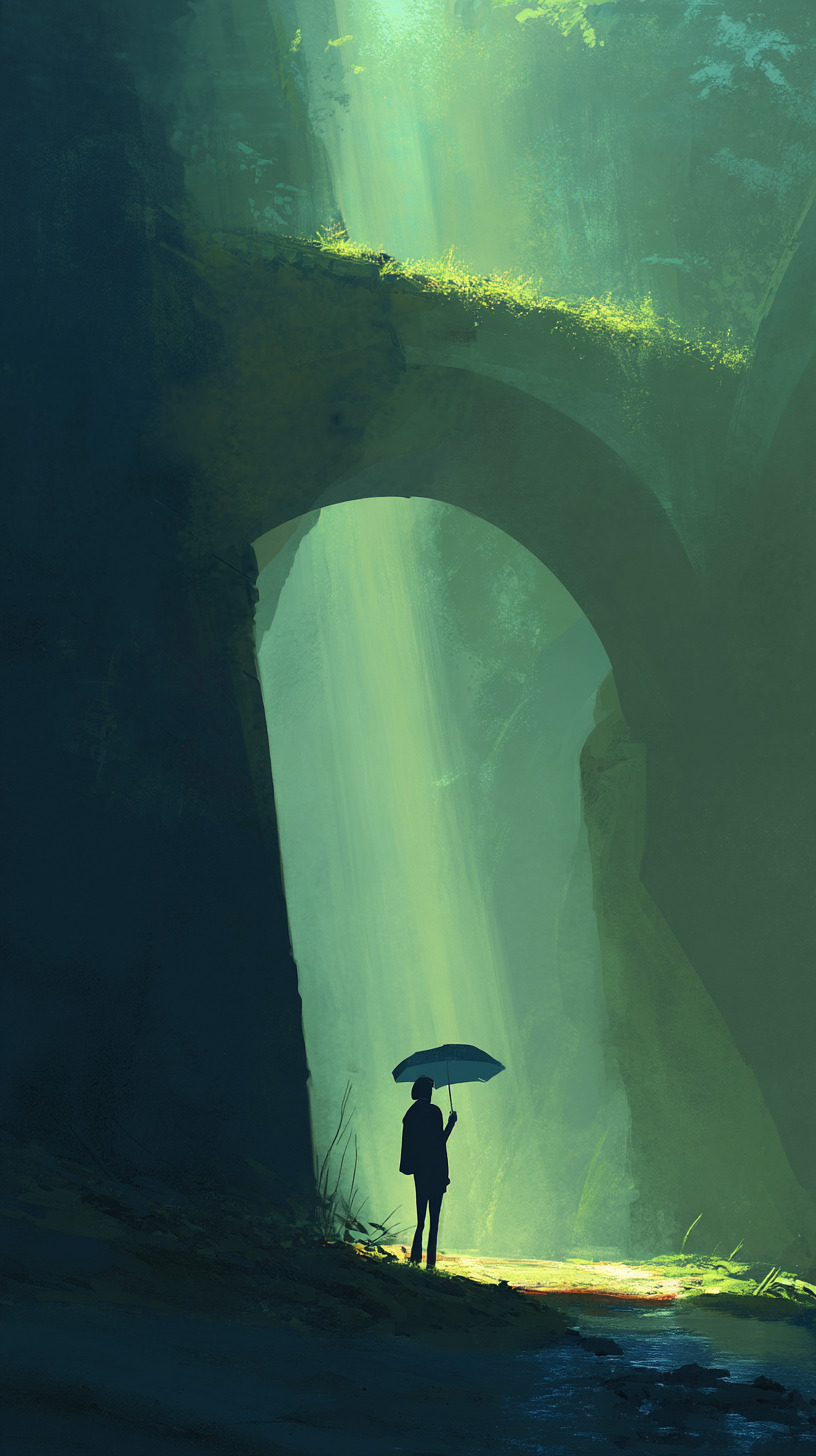

I want to wander through this world in awe of the beautiful unimaginable symmetry and complexity within it.

Lost to wonder.

I share new posts on my newsletter. If you liked this one, you should consider joining the list.

Have a comment or response? You can email me.