Earlier this year, I started thinking about software systems the way that theoretical physics thinks about physical systems – as a set of interdependent variables governed by invariants. What would it look like to study complex software systems from a first-principles, physics approach rather than a systems-design perspective?

Complexity and state in software and physics

The first question I asked myself was, what are the parameters of a software system?

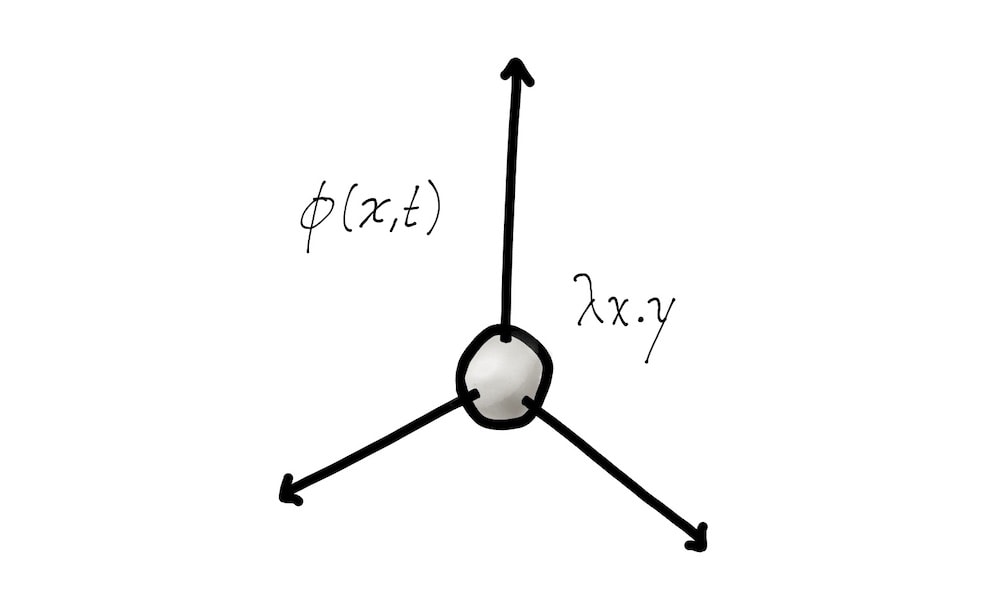

A physical system is fully described by some set of variables we call state. In classical physics, the state of a single particle, for example, includes its position in space as the x, y, z coordinates, plus its momentum. Given these properties of a system, we can use the invariants we know about how nature behaves to solve for future or past states of the system (the particle) in question.

(Aside: Our modern understanding of state is slightly more nuanced. A state in quantum mechanics is described as a kind of a composite of multiple different states with their associated probabilities. But for sake of our argument today, we can ignore this pedantry, and pretend as if a physical system is fully described by a set of numerical variables we call its state.)

The more complex a physical system is, the more parameters are required to fully describe its state. Complex systems have complex states, with many variables. This is mirrored in software. Take a simple snippet of a C program that counts from 0 to 9:

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i ++) {

printf("%d\n", i);

}

This program has one state variable, the counter i. We can fully describe the state of this piece of software at runtime by specifying the value of i.

Things get a lot more interesting when variables interact with one another. Take a double-for loop like this, counting 0-9 ten times.

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i ++) {

for (int j = 0; j < 10; j ++) {

printf("%d, %d\n", i, j);

}

}

There’s two variables here, i and j, and we need to specify both variables to fully describe the state of this program. Given that full state, we know exactly where the program is in its execution, and where it’s going to go next. Some programs might even be fully described with zero variables, like an infinite loop:

do {

printf("Hello\n")

} while (1);

We can fully describe this program’s state without specifying any state variables, because this program only has one state. It always does the same thing, and it always will.

In physical systems, we sometimes refer to the number of variables that fully describe a system’s state as the number of degrees of freedom. In this sense, we could say that the first program above has a single degree of freedom; the second program has two; and the third has zero. By comparison, an unmoving particle in 3-D space might have three degrees of freedom – the three coordinates required to describe its place in space.

Software degrees of freedom

One of the primary tasks in physics is to reduce complex systems into simpler problems by composing together simpler rules we know about nature. As a result, physics has found a bag of tricks we can use to take a complex system with a seemingly huge number of different states, and reduce such descriptions down to smaller problems.

A classic, beautiful example is the harmonic oscillator, what normal people call an ideal pendulum. At first glance, a pendulum with a weight at the bottom has many variables. It has the x, y, and z coordinates of the weight in space, alongside perhaps the angle of the pendulum.

But in reality, a (idealized) simple harmonic oscillator really only has one degree of freedom – the angle of swing. That’s because once we know the angle of swing at any given time, we can use the invariants we know about how a pendulum works, like the fact that the weight swings in an arc with a fixed radius, to figure out the position of the weight in space.

It may seem as if a SHO has many state variables, but there are constraints, such as the geometry of a circle, that we can use to simplify the space of possible states. In this way, the SHO becomes a beautifully simple physics problem that can model an endless variety of real-world phenomena accurately, from waves to subatomic particles to planets in orbit.

The important observation here is: invariant laws about a system constrains its degrees of freedom, making the system easier to understand and predict. The invariant laws do this by describing how different variables relate to each other in predictable ways.

Complexity and coupling

Another way in which state spaces are simplified is by making systems independent from one another. A classic example of this is the double pendulum. A single pendulum is one of the simplest physical systems to imagine, with an equally simple mathematical description. A double pendulum, however, behaves by much stranger rules, and its path in time quickly diverges in inscrutable ways. Simply making two systems depend on the state of each other has broken our ability to reason effectively about them. If they were independent systems, we’d be able to study them with ease.

In the same way, software systems that may be simple to understand in isolation quickly decay into unpredictable spaghetti when combined in intertwining ways where one depends on the state of the other. Rather than simply studying the smaller programs in isolation, we now have to model the entire, more complicated system as a whole, which quickly spirals out of our reach.

So much of software engineering is the study of taming complexity. Large modern codebases have millions of variables that combine to an unimaginable number of possible states for a program. In response, computer scientists – specifically compiler writers and programming language designers – have focused on ways to tame that complexity by doing the same thing physicists do. They introduce invariants that constrain state spaces of programs.

Types are constraints on software states

The most common way programmers introduce constraints in their programs is a program’s type system. In the same way that geometric and physics formulae constrain variables of a physical system, effective type systems constrain variables in a software system. In fact, I think that the effectiveness of a type system should be measured by how effectively it constrains the state space of a software system – by how much it reduces the marginal complexity introduced by a single new variable.

Take Rust’s type system, for example. If a variable has the type i32 (a 32-bit integer), that type constrains the possible values of that variable to a much smaller subset of valid values. Unlike dynamically typed languages like Python, where a variable that looks like an integer can be None in an unpredictable way, Rust’s type system introduces a constraint that we can trust to be an invariant of our software system, by way of the compiler’s type checker. This constraint, in turn, reduces the possible states of any expression that contains that variable. The reduction of complexity like this propagates through a software system, so that when these smaller programs are composed into much larger, more complex systems, the state space is still comprehensible.

The type system, like the laws of physics, is a small but versatile sword with which we enter the battle against exploding complexity in large interacting systems.

There are, of course, more obscure constraints languages place on their variables to reduce a program’s state space in more sophisticated ways. My favorite is ATS, a research language with absolutely mind-blowing(ly complex) syntax, but an equally advanced type system that worries not only about the possible values of individual types, but the relationships between individual variables’ values and the availability of resources like allocated memory, file descriptors, and array indices.

The battle that lies before us

The success and elegance of theoretical physics is rooted in mathematics’s ability to tame large-scale complexity by breaking down state spaces of complex systems into smaller, more understandable ones with simple laws. I think the challenge presented in software engineering is the same in many ways: taming the exploding complexity in large, abstract systems by discovering and introducing mathematical rules that reduce them into smaller, more understandable components.

The type system, the borrow checker, the static analyzer, the API – these are the tools we’re collecting as an industry in this battle against software complexity, and I think it may do us some good to examine how other fields also grapping with complexity wield mathematics in their fights.

Interesting things about the Lua interpreter →

I share new posts on my newsletter. If you liked this one, you should consider joining the list.

Have a comment or response? You can email me.