As we use any kind of tool over time, we naturally want the tool to work better for us, to fit our workflows and our use cases. The more we use a tool as a part of our day to day work, the more important it is that the tool work exactly the way we want to work with it.

Sometimes, we have the luxury of designing and building a tool that’s tailor-made for exactly the workflows and use cases we need. When we can, it’s usually the best option. Large companies that can afford internal engineering teams invest heavily into building business tools that nobody outside of the company would ever use, because having that perfect fit between your tools and workflows matters. For a hobby developer like me, this is also sometimes a good solution – most of my tools I use day to day to get things done are home-brew, and built to fit exactly around how I work.

Most people and teams don’t have this luxury of building a tool just for one use case, though. Instead, someone else makes the tool for lots of people, and you get one copy of the tool. But even then, individual tool-users might have their own use cases they want the tool to fit better. The simplest, most conventional solution to this problem of a single tool-maker serving many different workflows is simple customization: the tool comes built-in with a bunch of levers, dials, and switches you can control, and each user gets to tune these controls to get the tool to behave exactly how they want it. These can be simple and intuitive, like the volume dial of any speaker system, or complicated, like the multi-page settings pane of a professional audio workstation or video editing program.

Customization is one solution to bringing our tools closer to our use cases, but it has a few problems.

- Customization only happens at the start. The tool-maker needs to anticipate all the different ways that the user might want to change the tool, and bake it into the tool from the beginning. You can’t tweak something about a tool if it never came with a dial for it.

- Customization doesn’t scale. The more flexible you want the tool to be, the more complicated the options become. When building a tool for power users, like a video editor or an IDE for software development, you end up with pages and pages of customizable buttons and options, which add flexibility at the cost of immense complexity.

- Customization creates a learning curve. Every option added to a tool is an option that a new user of that tool needs to learn to take full advantage of the tool. The more powerful the tool gets, the steeper the learning curve.

All of these problems become worse as a tool becomes more powerful and flexible. When a tool is designed to be simply customizable with an abundance of settings and options, adding power means adding complexity and steepening the learning curve. If great tools are about multiplying our creativity, customization gets in the way of this mission, because it limits how flexible our tools can be, and how easily we can learn to use them. We need a better way to build tools that wrap around our workflows than simply adding levers and dials for every new option.

Grow, don’t customize

When a tool is monolithic, with one way to work and little to customize, people who use the tool end up growing around the tool. They learn the tool’s various quirks and sharp edges, and learn to avoid and work around them. Because the tool itself is so rigid, the human has to change to bend their workflows around how the tool works. This is the worst of all worlds.

More charitable designers will let a tool be customized to the liking of those who wield its power. As I noted before, this allows the people who use a tool to change the tool to fit their needs. Rather than the human growing workflows around the tool, they bend the tool around how they work by tweaking the dials and options that came with the tool. This works, but we saw the ways it falls short.

In either case, we try to develop a relationship between a tool and the people who use it by holding one fixed, and trying to bend the other to fit. But the best relationships between a tool and its users, as in any good relationship, is about growing and changing together. I think we need tools that grow naturally alongside their users through use.

Here, I mean “grow” in the way that an ivy grows, by exploring its surroundings and intertwining itself with the world around it, not “grow” as in scale. Humans and tools form a symbiosis in the best cases, and that relationship works best when tools can change over time as their users explore their craft through the tools.

My favorite example of a growable tool is the pair of canonical terminal-based text editors, Emacs and Vim. Different as they are in the small, at a high level, the popularity and longevity of these text editors in the software industry come from the same core idea: both text editors are built around the idea of building “scripts” or repeatable sequences of action that can be live-programmed in the editor, saved, and played back later. In Emacs with Emacs Lisp and in Vim with macros, a programmer can call commands and run through actions in the text editor, and if it’s useful, they can save it as a program or a macro to run again later. Over time, expert Emacs and Vim users accumulate a collection of handy functions and macros that becomes a part of the way they work with the text editor. These small programs that collect over time are neither a part of the editor, nor purely a part of the user. It’s the result of a collaboration between the tool and the tool-user. Over time, I’ve grown alongside my Vim editor’s configuration, and as much as Vim has changed how I edit programs, I’ve also contributed to my version of Vim lots of shortcuts and macros I use every week that has changed how Vim works for me.

To guide our thinking about other growable tools, let’s understand what goes into a tool that can grow with its users.

Principles for growable tools

There are three critical pieces to building a tool that can grow around its users over time.

-

Design around play. Sometimes I call this design around experimentation. Using the tool for day-to-day work should involve playing and experimenting with what’s possible with the tool. Whether that’s writing small programs to edit text more quickly in Emacs, or discovering a new chord progression you want to use later, experimenting with features should be a core part of the way the tool is designed to be used.

-

Make it easy to save experiments to re-use later. Whenever we discover an interesting chord progression or a useful editor shortcut in the course of our daily play with the tool, we should be able to save it to invoke it later. The easiest way to do this is to offer some text representation of an action, so the string of text can be saved and re-run later. The power of a growable tool really comes from the seamless flow from experimentation to collection of neat tricks and small workflows. You need both parts.

A web browser is a great example of a tool that’s heavily customizable, but falls short of growing with users because of the lack of this seamless flow between play and save. Modern browsers all admit extensions that we can use to customize how the browser works in deep ways, but these extensions are too complex for us to write while using the browser day-to-day. It’s impossible to go from “let me try to do this” to “this is useful, let’s save it for later” with a browser extension. Writing an extension is a fundamentally different job than using the browser, and the browser fails to grow with users because of this disconnect. Imagine if you could write small 2-3 line programs while browsing the web that changed how the browser worked for that particular page, and then save those snippets to pull up and re-use later. Wouldn’t it completely change how you interact with your web browser?

-

Add power by combining simple parts that work together, not adding options. This is better known as the UNIX philosophy, which states:

Write programs that do one thing and do it well.

Write programs to work together.

Write programs to handle text streams, because that is a universal interface.In other words, make big tools by combining smaller tools with small focuses that work together well and understand each other. When we build a tool as a system of smaller tools that work together, it becomes much easier for users to play and experiment with new workflows during their everyday use. “Scripting” within the tool becomes natural, as we’ll see below.

A tool built with these principles in mind can offer just as much flexibility as the most configuration-saturated tools in the world, without succumbing to the same pitfalls. Because users tweak and change the tool by experimenting over time, customization happens constantly, not just at the beginning. Because the customization happens by mixing and matching small patterns that work together, users only need to learn that small set of primitives to get started using the tool like a power user. Growable tools scale with power in a way customizable tools don’t.

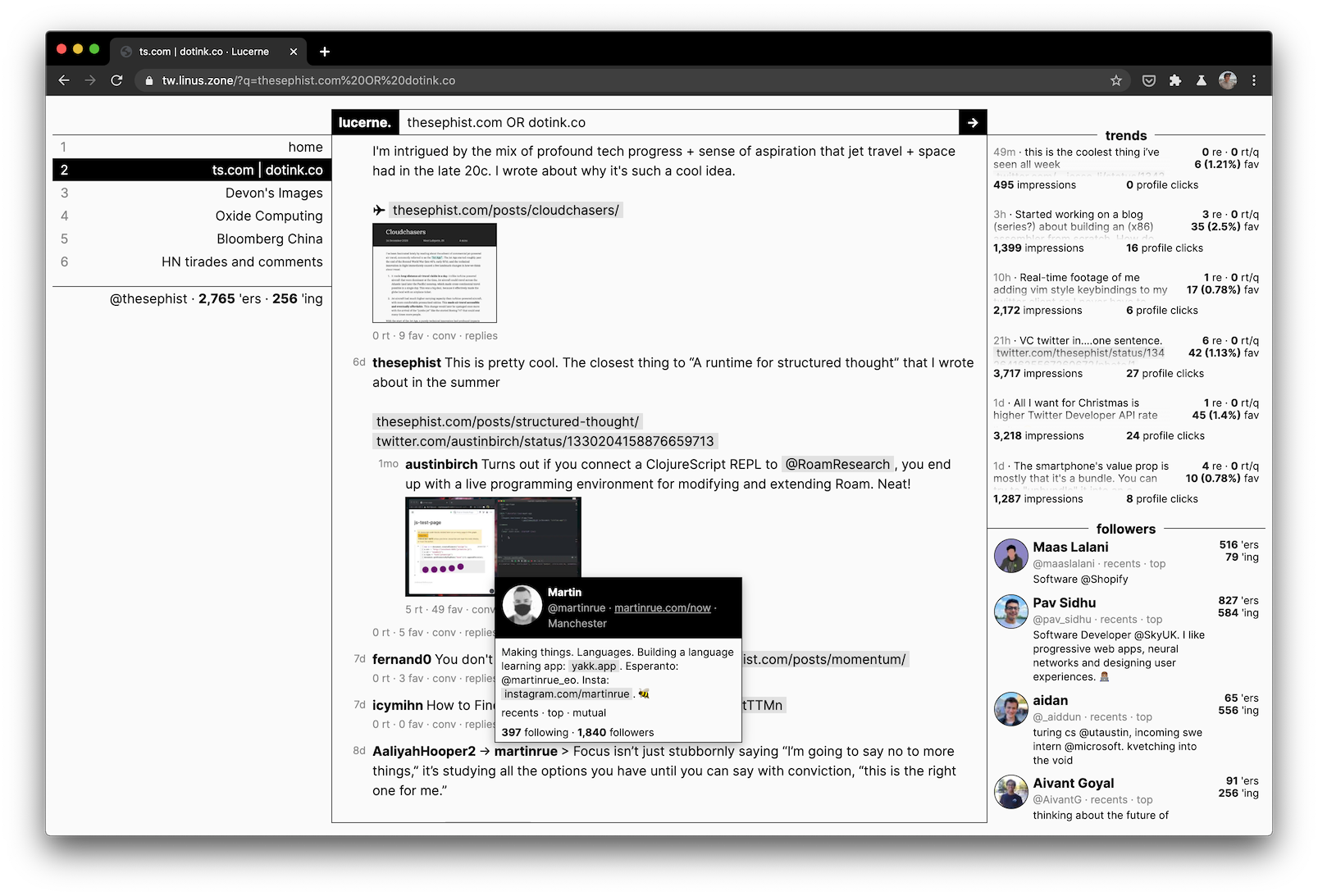

I recently built a Twitter reader and client, Lucerne, as a Twitter reader that could grow with me. Twitter’s default experience is far from a collaboration between me and the app. Despite the wealth of information that floats through the ether of the Twittersphere, the app feeds me a small sliver it wants to deliver, and I passively scroll. Lucerne is built around the idea of channels, or saved searches. As I use Lucerne, I can explore Twitter by searching for keywords, ideas, and users through threads on Twitter with an array of filters. If any filter seems particular useful, I save that filter as a “channel” pinned to the sidebar that I can come back to later. The more I use Lucerne to browse Twitter, the better channels I’ll collect. Eventually, Lucerne will grow a long list of channels that define how I use Lucerne, more than simply how the tool works.

Within Lucerne, each search query is a combination of small filters, like filter:retweets to see only retweets, re:123456789 to see a reply to a tweet, or from:thesephist to see a tweet by a particular account. These can combine to build more complex queries like “most popular tweets by X account on Y topic” (sort:top from:thesephist #topic). Rather than having a built-in feature, building up this search system from small parts that work together leaves open many more possibilities for experimentation and play. I’ve started curating a small collection of channels I check every day through Lucerne, and I’m looking forward to using it more.

There are still so many areas of work filled with tools that are merely customizable, but don’t grow with use. Web browsers, video editors, word processors, digital instruments… these are all huge categories of tools where the tools offer a dizzying array of configuration options at best. Expert video editors or instrumentalists spend years dialing in the tools to work the way they’d like, and the tools rarely reciprocate by growing around their users. If we want these crafts to truly be powerful amplifiers of human creativity, we need them to be more learnable and more flexible than they are today, while becoming even more powerful. We can only get there by building tools that grow around us as we use them to explore what’s possible, towards an ever-changing symbiosis between people and the tools that bring their ideas to life.

Many ideas in this post have been explored in a million different directions by some of the best designers and tool-builders through history, on whose shoulders I hope this idea stands. If you’re also interested in building better tools, my thoughts are inspired by

- Alan Kay

- Bret Victor

- Chris Granger

- Geoffrey Litt

- Lea Verou

- Omar Rizwan

- Rich Hickey

… and many others.

← Laws of individuals, laws of masses

Building Lucerne, a Twitter experience tailored to me →

I share new posts on my newsletter. If you liked this one, you should consider joining the list.

Have a comment or response? You can email me.