Everybody seems to generally agree: it’s important that today’s students have access to coding or computer literacy education. Not everyone agrees on why, what kind, or at what cost.

Within the sphere of the technology industry and the maker circles around me, the dominant argument seems to focus on the creative power of coding. We say coding is a superpower. With code, you can build things that the world can use, from the comfort of your bedroom. We like to point out the barons of the information industry, and how much of the foundational software that runs today’s Internet economy was built by code jockeys and side-project hustlers who now stand atop our economic engine, and how learning to code is an essential piece of their story.

Code is the creative tool of this century. It amplifies an individual’s intent infinitely at basically zero cost. This is a great reason why we need to broaden access to coding education, so every middle school and high school student has the choice to learn to code, just as they learn to play music in school. I call this weak sort of argument for universal accessibility to coding education the access problem.

But I think the fact that code is a powerful creative tool falls short as an argument for universal computing literacy. I believe that learning about how computers and the Internet works at a basic level is as important as learning to read critically, because the scalability of software means code is also now the most powerful tool for distributing power and influence in the world. And like linguistic literacy, I believe this should be a part of every student’s education. It should be truly universal and compulsory, not a choice. I call this stronger argument the universal literacy problem.

Others have made great arguments in support of solving the access problem. Here, I want to articulate and emphasize why I think a more important and pressing problem is that of universal computing literacy.

Literacy

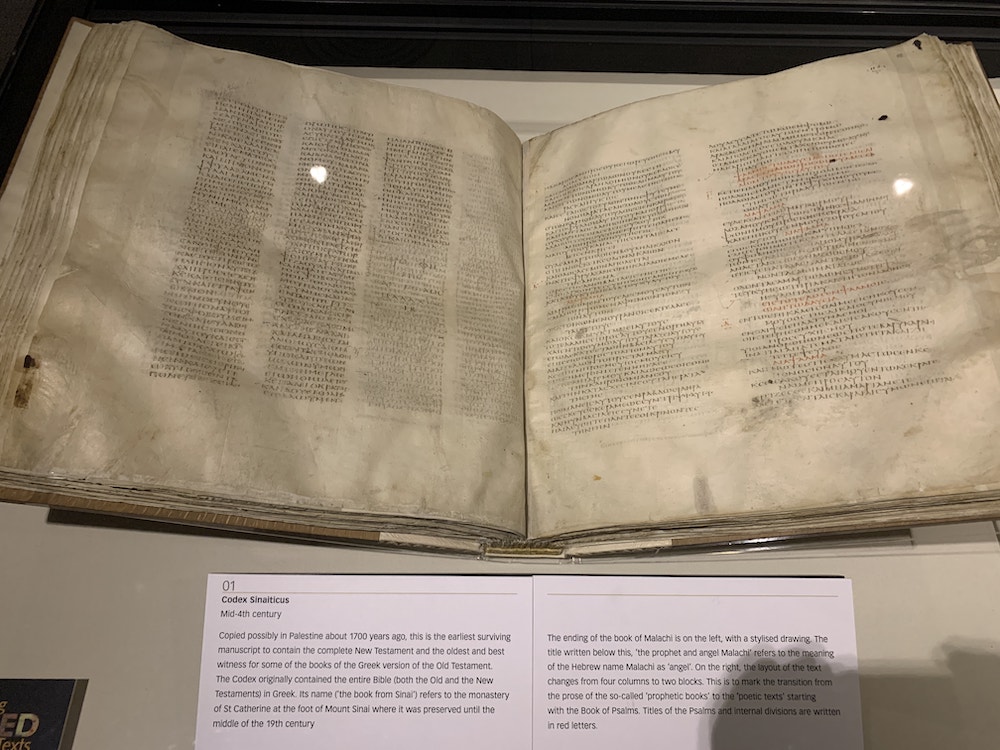

Earlier this year, I visited the The British Library’s exhibit of old books and manuscripts. Their collection includes books from the 4th century, handwritten letters from the Second World War, and the Magna Carta. Walking through the room, I was struck by a realization so obvious in hindsight. These books were all written by hand.

For the overwhelming majority of recorded history, writing was a manual craft. It’s amazing just how detailed and intricate of artisanal artifacts books were before. They were the antithesis of commodity, covered in gold films and filled with decorative paintings that must have taken hours of error-prone labor per page. Books, and as a result, knowledge, were luxury goods.

Then came the printing press, then computers, and the automation of publishing and printing, and then the Internet, the last few in rapid succession. The changes that these inventions sent rippling throughout the world all have their origins in changing just how cheaply and quickly knowledge and power are distributed. This broad availability of writing, combined with a global trend to lift literacy rates amongst the general public, meant that the public were increasingly able to have opinions about the voices in power, able to cheaply organize and scale collective action, and drive widespread social change.

Printed pamphlets spread the voices behind some of the cornerstone social and political movements in recent history, from the Protestant Reformation to the American Revolution and debates across the Atlantic about the French Revolution. But as technology claimed more of popular culture and life, it also made the medium of these distributions of opinion and knowledge more opaque. It’s trivial to wrap our minds around how words are printed on a pamphlet, or how a nationwide televison program is broadcast, but modern political and social rhetoric takes place behind algorithmic social feeds and filter bubbles that require technical degrees in the front lines of data science research to understand properly.

I think this trend is only going to accelerate, and our standard for literacy has to step up to the times. In 2020, understanding how computers work, and where their limitations lie, is as essential to effective literacy as critical reading and logic, and we should treat it with such importance.

After writing the initial draft of this post, I found a talk on coding curriculum design by Prof. Shriram Krishnamurthi from Brown, which tops my list of the best talks I’ve watched on scaling computer science education. It’s not particularly relevant to the topic I discuss here, which is why I only mention it as a footnote, but if you’re interested in this area, I recommend it.

I share new posts on my newsletter. If you liked this one, you should consider joining the list.

Have a comment or response? You can email me.